MMD Design and Consultancy Limited v Camco Engineering Pty Ltd

[2023] FCA 827

Justice Rofe (21 July 2023)

The repair defence

It is just shy of three years since the High Court handed down its decision in Calidad Pty Ltd v Seiko Epson Corporation (2020) 272 CLR 351 regarding the “exhaustion doctrine” and the “repair defence” to patent infringement. Since then, that case has received judicial consideration just three times, and for the first time substantively by Justice Rofe in a patent dispute between MMD Design and Consultancy Limited and Camco Engineering Pty Ltd.

In Calidad, the High Court was required to determine whether a purchaser of a patented product held an implied licence from the patentee to use the product, or whether the rights of the patentee to exclude full use of that product were exhausted upon it being sold to the purchaser. The majority of the High Court held that the “implied licence doctrine” should be abandoned in favour of the “exhaustion doctrine”.

But, regardless of which doctrine applied, the majority in Calidad observed that the “sale of a patented product cannot confer an implied licence to make another and it cannot exhaust the right of a patentee to prevent others from being made”: Calidad at [45]. The High Court considered whether Calidad’s modifications to Seiko’s depleted printer cartridges were within the scope of a purchaser’s rights to repair what it owns, or constituted a making of the patented cartridges, which would be an infringement of Seiko’s patent monopoly.

As Justice Rofe observed, the crucial question is “whether a party has engaged in a permissible repair or an impermissible manufacture”. The majority in Calidad found that the modifications Calidad made to the used printer cartridges were not an infringement of Seiko’s patent. In so doing, their Honours observed, and Rofe J in MMD v Camco emphasised at [407] (her Honour’s emphasis):

66. …The question of infringement under the Patents Act 1990 is not addressed to the nature of the article but rather to the invention described by the integers of the claim. Where what has been done does not involve the replication of the combination of integers that describe the invention it cannot be said that what has been done is the making of it.

67. When a small hole was made in the printing material container of the original Epson cartridge to enable it to be refilled with ink, the cartridge did not cease to exist, and it was not made anew when the two holes were sealed. The product did not cease to exist when the memory chip was substituted. An argument that an article has been “unmade” and then “remade” might have some weight in a circumstance such as United Wire. However, it is somewhat artificial in cases where parts are changed so as to permit continuation of use. In Wilson v Simpson, referred to with approval in Aro Manufacturing, the Court refused to accept that a tangible machine could be said to have ceased to have a material existence because a part that had become inoperative was repaired or replaced. …

69. When all of Ninestar’s modifications to each of the categories of cartridges were completed what remained were the original Epson cartridges with some modifications which enabled their re-use. The modifications did not involve the replication of parts and features of the invention claimed. There was no true manufacture or construction of a cartridge which embodied the features of the patent claim.

As to the United Wire case referred to above, the majority in Calidad at [51] observed:

… The patent there in question concerned improvements to sifting screens used to recycle drilling fluid in the offshore oil-drilling industry. The screen was described in the first claim of the patent as a sifting screen assembly, comprising a frame to which mesh screens were secured, for use in a vibratory sifting machine. The defendants stripped down the screen to its frame and then secured new mesh screens to it. This was regarded by Aldous LJ, in the Court of Appeal, as equivalent to purchasing the frames on the open market and then using them to produce an assembly. The House of Lords held that the Court of Appeal was entitled to conclude that the totality of the work amounted to “making” a new article because the removal of the meshes and the stripping down and repairing of the frame resulted in a mere component of the patented article remaining “from which a new screen could be [and was] made”.

Now, it should be noted that, by reason of her Honour’s construction of MMD’s patent, Camco’s conduct did not infringe MMD’s patent in any event. Accordingly, her Honour’s consideration of Camco’s repair defence was strictly obiter.

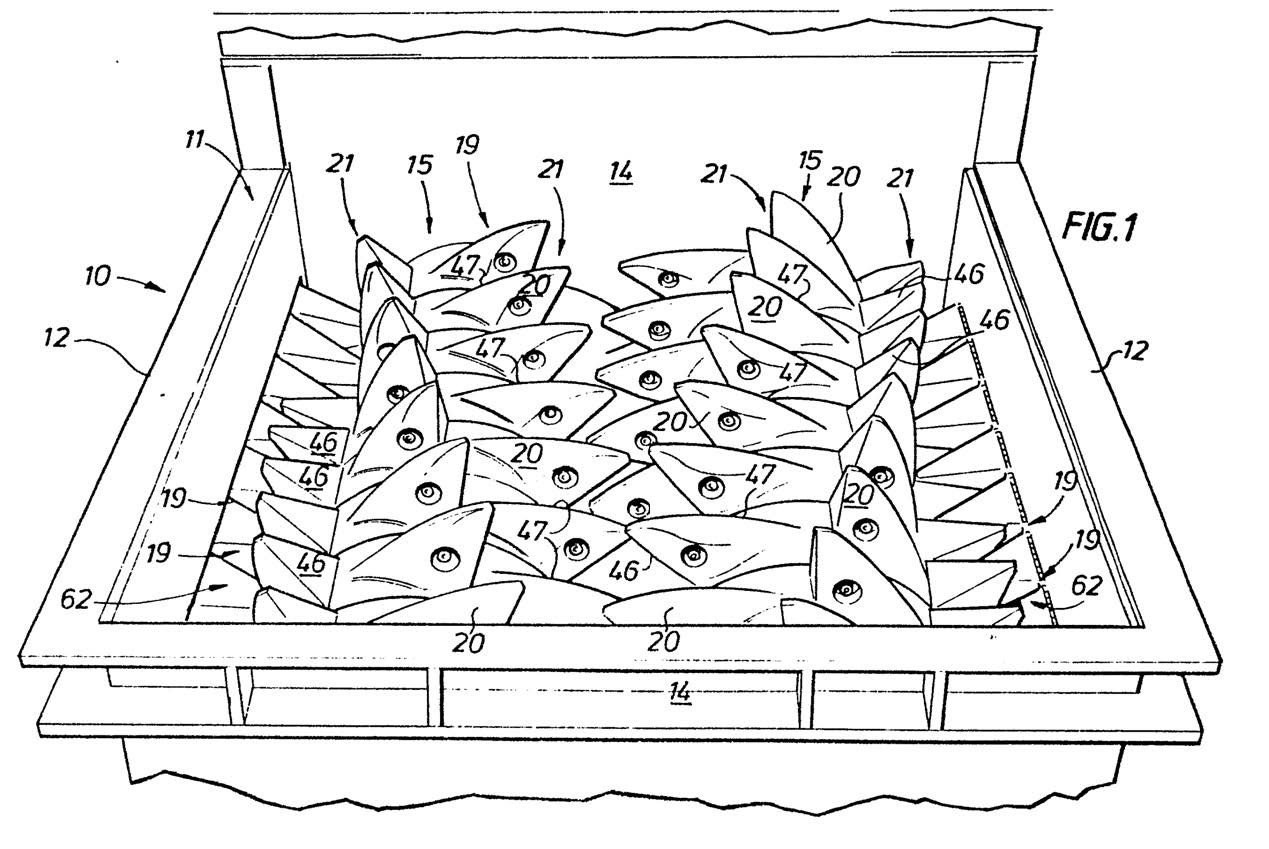

Turning to the facts of the case before Justice Rofe, mineral sizers (or mineral breakers) are large pieces of equipment, used predominantly on mine sites to break mineral ore into smaller sizes so that the rocks are a suitable size for further processing. Mineral sizers typically comprise two counter-rotating parallel shafts, with each shaft having a series of adjacent drums with radially projecting teeth which break up the incoming ore, the teeth from each shaft being off-set so as to be interlaced, as depicted below:

MMD’s patent concerns the construction of the teeth used in such a mineral breaker. In particular, the construction involves covering a tooth shaped support body with a shell made up of sacrificial covers welded to each other and/or the support body in a particular orientation, namely “a front cover which is weldingly secured to and seated in face to face contact with the front face of the support body and a separate rear cover which is weldingly secured to and seated in face to face contact with the rear face of the support body”. The primary debate between the parties lay in the proper construction of those quoted integers, but that is not the subject of this article.

Camco provides an after-market repair service, repairing parts of mineral breakers owned by mining companies. Camco explained that:

Repair of mineral breaker teeth is required because the components forming the teeth are consumable parts worn away by the mineral breaking process and need replacing after a period of time in use. Over the years, Camco has repaired tooth structures as part of the overall repair of breaker [sizer] shaft assemblies by using OEM parts provided by the mining companies, purchasing parts directly from the OEM, or by Camco manufacturing parts of its own, or by Camco using welding and other hard facing techniques that do not require spare parts.

The sizer shaft assemblies typically arrive at the Camco workshop by truck on transport frames and are delivered back to the mine site for reinstallation in the mineral sizer following refurbishment.

Her Honour observed that “the only part of the claimed invention which is not replaced by Camco when undertaking a refurbishment is the tooth-shaped support body”. Once “the covers of the tooth construction are removed via arc gouging of the weld, all that remains is the naked support body attached to the sizer ring” and “the fact that this ‘skeleton or chassis’ remains does not derogate from the conclusion that Camco has unmade the patented tooth construction and made a new tooth construction”. Her Honour concluded that the “shell of the tooth construction has ceased to exist at this point” and that “each of the covers that form the shell was removed and replaced with new covers, rather than the cover being repaired and re-used”.

Justice Rofe observed that the claim was to a tooth construction for a mineral breaker, not to a mineral breaker that included, among other things, tooth constructions. Interestingly, her Honour appeared to be of the view that, if the claim was to a mineral breaker, the reconstruction of the tooth constructions might have constituted a permissible repair. But the refurbishment of the patented tooth construction went too far, replicating the integers of the claim which related to the welding connection between the covers and the support body. Therefore, the repair defence would not have been made out, if there had otherwise been an infringement.

Hindsight bias in inventive step evidence

Dr Huggett, called by Camco, was shown MMD’s patent before he was provided with any of the prior art. None of that prior art formed part of the common general knowledge of the person skilled in the art. Dr Huggett was not aware of problems with bolted tooth constructions at the priority date and only became aware of that problem upon reading the prior art that he was given. Indeed, the prior art itself did not identify any problems with the use of bolts.

Accordingly, Justice Rofe found that Dr Huggett’s evidence as to what he considered would be the obvious design of a robust tooth construction, overcoming an unknown (non-common general knowledge) “problem” of using bolts to secure the covers to a support body by using welding, was “impermissibly assisted by hindsight”:

Whilst bolting and welding may have been examples of well-known methods for attaching components to equipment in the mining industry at the priority date, the use of bolts or welding to attach covers to mineral sizer teeth/horns, particularly for use in hard rock crushing was not part of the common general knowledge

Having read the Patent before giving his evidence it is not surprising that Dr Huggett chose the welding route rather than bolts.

The authors note that, while they are aware that the Federal Court is taking steps towards relaxing the extent to which an expert must be quarantined from the patent when drafting inventive step evidence, this case highlights the need, if nothing else, to explain to the expert the danger of such bias and how it may be addressed or sought to be avoided. Further, this case suggests that additional care should be exercised in cases where “the problem” might be argued not to be common general knowledge.