Attempting To Collude Won’t Fly

ACCC v Flight Centre Limited (No 2) [2013] FCA 1313

In 2012 the ACCC successfully took Flight Centre to court for attempting to collude with three international airlines. This case is a very rare example of the ACCC making use of the law of attempted collusion (rather than actual collusion).

Facts

Flight Centre Limited operated, via a subsidiary, a chain of popular retail travel agencies in Australia. It was the largest brick-and-mortar retail travel agency in Australia. It contracted with international airlines to arrange, on behalf of those airlines, international air travel with customers who walk into Flight Centre’s retail shop-fronts. Flight Centre also handled the payments of such customers, passing them on to airlines. For these services, Flight Centre received commissions from airlines.

The commissions took two main forms. The first form was that Flight Centre could keep any excess over a minimum fare (the ‘nett fare’, set by an airline) which Flight Centre was able to sell to the customer on behalf of that airline. The second form was a pre-agreed fixed payment, made by an airline to Flight Centre, for each ticket sold on behalf of that airline (the commission).

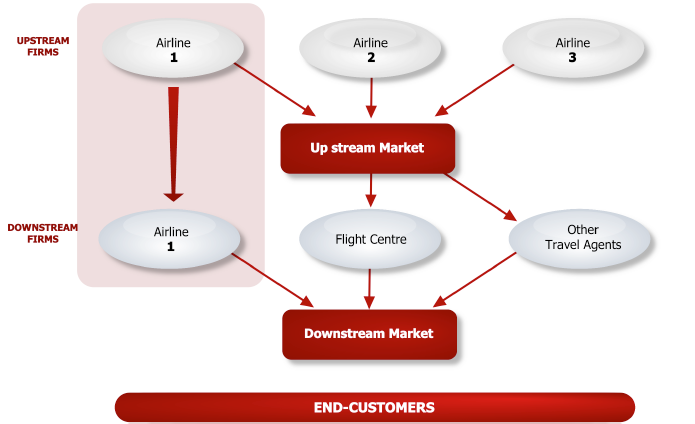

During the 2000s, the rise of the internet meant that international airlines could deal directly with customers via their own webpages. This direct-sale channel enabled international airlines to bypass, at least in part, the Flight Centre sale channel. For the purpose of competition law, it also meant that international airlines were now competing in the same (‘horizontal’) market as Flight Centre for end-customer sales, a market in which, depending on how you measured it, Flight Centre had a market share of about 30 percent. This is broadly shown in the following schematized diagram.

TRAVEL SERVICES INDUSTRY WITH FORWARD INTEGRATION

During the period 2005 to 2009, in the course of negotiating new contracts with three international airlines (Singapore Airlines, Emirates, Malaysia Airlines), Flight Centre sought agreement for a provision which would ensure that, whatever fare was offered by the three international airlines via direct sales to end-customers, would also be available for Flight Centre to offer to end-customers. In particular, Flight Centre required that the three airlines only offer, when selling directly to end-customers, a total price not less than the sum of the ‘nett fare’ plus the commission. Negotiations over these contracts were robust, including threats by parties on both sides of the proposed contract to walk away from the relationship.

Law

The ACCC issued proceedings in the Federal Court in Brisbane in 2012, alleging that Flight Centre attempted to induce the three international airlines (Singapore Airlines, Emirates, Malaysia Airlines) to enter into a contract with Flight Centre, where the proposed contract contained a price-fixing provision. Broadly speaking, entering into a contract containing a price-fixing provision was prohibited by ss 45 and 45A of the then Trade Practices Act 1974 (the Act) [now the Competition and Consumer Act 2010]. Price-fixing includes controlling or maintaining prices [158]. Attempting to induce another person to contravene ss 45 and 45A was prohibited by s 76(1)(d) of the Act, which empowers the court to impose a pecuniary penalty on the offending person for each attempt. Inducement under the Act can be effected by threats or promises (s 76(1)(d)). The ACCC had the civil burden of proof, to which the Briginshaw principle applied [8].

Decision

Logan J found for the ACCC on each of the six alleged contraventions brought before the court ([161], [166], [171], [178], [189], [196]). Logan J found that email correspondence, from executives at Flight Centre to executives at each of the three international airlines, contained implicit and explicit threats of either withdrawal of services or else the steering of end-customers by Flight Centre consultants to alternative airlines. Logan J concluded that this was evidence of attempts by Flight Centre to induce entry into the proposed contracts ([154]-[157], [165], [170], [177], [187], [196]).

A hearing to determine penalties lies ahead.

Impact of case

This is a very rare case of the ACCC going after a company for attempted collusion (rather than actual collusion). It is not difficult to recall some notable past unsuccessful litigation by the ACCC that might have had an alternative outcome by focussing on attempted collusion (rather than actual collusion). The law regarding attempt under s 76(1)(d) and the old s 45A of the Act still has relevance under s 79 and the new cartel provisions of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010, with the added bite of criminal sanctions.

Richard Scheelings – CommBar profile