Axent Holdings Pty Ltd v Compusign Australia Pty Ltd

[2020] FCA 1373

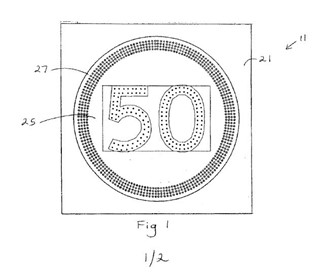

Axent specialises in the design, manufacture, supply and support of LED-based visual communication systems, including electronic speed signs on Australian roads. It is the owner of the patent in suit, one embodiment of which is depicted below, that has become somewhat ubiquitous on many major roads around Australia. The claims of the patent are to an electronic variable speed limit sign, which has a plurality of lights forming the central speed limit numerals and the annulus rings around those numerals and where there must be a variation of that display when a speed limit other than a “normal speed limit” is being displayed. Some dependent claims require the variation to be a flashing of a portion of the annulus rings.

Axent’s sole director, Mr Fontaine, claimed to be the inventor of the invention the subject of the patent. The market for speed signs systems in Australia included supply to road government authorities such as VicRoads. VicRoads would typically seek competitive tenders for road works and would prepare specifications for the products and systems that it seeks to have supplied to it. It was possible for a supplier to obtain a type approval for their product or system, so that they could supply it on an ongoing basis without having to go through an individual approval for every tender or contract. The process of obtaining type approval involved submitting a range of technical documentation and often product testing also. If a type approval is not in place then the relevant documentation is usually a requirement of the tender itself.

In around September 2000, VicRoads attended Axent’s premises to view the prototype for Axent’s variable speed limit sign. Mr Fontaine told VicRoads that Axent’s signage could be programmed to warn the driver of a speed zone change by flashing some but not all of the rings of the annulus around the speed limit number, and demonstrated that feature on a prototype that had been developed by Axent.

Then in April 2001, VicRoads called for expressions of interest for the Western Ring Road Project. A VicRoads specification for the supply and installation of electronic variable speed restriction signs dated April 2001 did not refer to any portion of the annulus flashing or to any need to warn of a change in speed. VicRoads told Mr Fontaine that Axent would need to comply with the VicRoads specification for the supply and installation of electronic variable speed restriction signs. A second specification was provided as part of the tender documents in September 2001 which provided that part of the inner diameter of the red annulus should be capable of flashing on and off.

While Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that he had never been asked by VicRoads whether his invention could be included in the VicRoads specification and he considered his invention to be confidential, he knew that the specification would be provided to competitors, he knew that it could form the basis of a “type approval” for competitors, and he was “not unhappy” that the specification included the requirement of having a flashing annulus.

It was not until October 2002 that Axent filed a provisional patent application, from which the patent in suit derived priority. Astute observers will at once appreciate that the VicRoads September 2001 specification would be an obvious contender for lack of novelty and possibly lack of inventive step, subject to the operation of section 24 discussed below. Those with a wily mind might also have considered whether persons engaged by VicRoads to install potentially infringing signs might have the benefit of the Crown-use provisions. These matters and more were all in issue in this case.

To add to Axent’s woes, Axent did not pay the renewal fees for its patent within time as required, and nor did it pay those fees within the additional six-month period of grace under the regulations. Accordingly, by operation of s 146(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), the patent ceased. Axent eventually made application for and obtained an extension of time to pay the fees in September 2016, but section 223(10) of the Act provides that no infringement proceedings can be asserted in respect of infringement during the period the patent was ceased. A debate then arose as to whether the patent was ceased from 6 October 2015 or the end of the six-month grace period, which Kenny J resolved in favour of Compusign.

But before turning to these curious defences and invalidity, there was the primary question of infringement and a debate about whether the claims were to a product or a process. The independent claims in the patent commenced with language that indicated that what was claimed was a product: claiming a “changing sign system for use […]”. Indeed, each independent claim also included features apt to describe the physical features of a product. But the claims further included language that described how the sign system would work “when the system is in use” and in a particular circumstance, namely “when a speed limit different to the normal speed limit” is required. The debate therefore centred on whether these further features were limitations by result (or functional limitations) apt for a product claim or were properly described as a mode of use apt for method claims.

After a careful review of the authorities and consideration of the independent claims (and dependent claims), Kenny J found that the claims were product claims, as Axent contended. Her Honour found that, although the expression “normal speed limit” could be regarded in some contexts as indicative of a method claim since the concept of “normal speed limit” might be read as specific to a particular location and time of use, “it seems to me that the expression “normal speed limit” is used in a normative sense so as to mean “conforming to the usual standard on the roadway” wherever located”.

However, her Honour disagreed with Axent that the claims look to “capabilities” of the sign systems, instead finding that the claims identified what must be “physical characteristics” of the sign systems. Her Honour therefore accepted, by way of example, that the claim integer, “wherein the sign system fulfils the criteria of being a speed display system by always showing a number in a circle on the display panel, when the system is in use”, is not framed in terms of capability as to how the sign could operate, but in terms of how the sign will in fact operate. This finding appeared in part relevant to the respondents’ case in defending the direct infringement case.

Turning to the allegedly infringing products (of which there were a few) and the various claim integers, her Honour found that numerous integers were not present. As noted above, the independent claims required that “the sign system fulfils the criteria of being a speed display sign by always showing a number in a circle on the display panel, when the system is in use”. However, the allegedly infringing signs do not always show a number when in use. Her Honour observed that for some of the signs, “even when connected to a power source, the signs will show a blank display unless and until they receive (and continue to receive) directions from the operator’s command centre” and other signs could show other displays such as indicating a change of lanes.

Therefore, while the infringing signs no doubt had the “capacity” to always show a number, they were not inherently designed to do so. Kenny J observed (with respect to a similar integer) that “[t]he fact these signs were capable of achieving these results if the operator made the appropriate selections does not establish that, when the sign system is in use, the features of the sign were necessarily such as to fulfil these functional limitations or achieve such [claimed] results”.

Turning then to Axent’s section 117 infringement case, originally Axent’s case was that the supply of each of the allegedly infringing signs was, in addition to a direct infringement, an indirect infringement pursuant to section 117 of the Act. Accordingly, her Honour found that that case was in effect no different to the direct infringement case and failed for the same reasons. However, her Honour also observed, in obiter, that “it is unlikely that a primary infringer of a product patent could be, by the same act, also liable for contributory infringement under s 117”. Her Honour there identified a debate on the proper construction of section 117 that may yet find some interest in future cases.

Turning to the various defences, Kenny J considered the Crown-use infringement exemption in section 163 of the Act as it applied to the case at hand (not as presently enacted). After addressing the authorities, Her Honour accepted that each of VicRoads, and other authorities in issue, was a relevant “authority of the state” as required by section 163. Next section 163 required that the invention have been exploited for the services of the authority of the State. Section 163(3) of the Act stipulated that “an invention is taken for the purposes of this Part to be exploited for services of the Commonwealth or of a State if the exploitation of the invention is necessary for the proper provision of those services within Australia”. Kenny J observed that, absent s 163(3), the exploitation of the signs by each of the three authorities is for the services of each of them. However, her Honour was concerned that it might be said that such exploitation was not necessary in the sense contemplated by s 163(3) because alternative signage was available and widely used. Ultimately, her Honour did not need to rule on the point because she found that another requirement of section 163 was not met by the respondents.

Section 163(1) provided that the Crown-use exemption would extend to a “person authorised in writing by the Commonwealth or a State” to do the infringing act. The relevant respondent contended that a document evidencing a contractual supply was sufficient to amount to an authorisation, and that an otherwise infringing supply to an authority in circumstances where the infringer received a written purchase order or other request to do so was sufficient to constitute a written authorisation. Her Honour disagreed. While the authorisation could be express or implied, but had to be an “actual” authorisation and her Honour considered that it was necessary that the written authorisation not leave it open as to whether the infringer could supply a non-infringing article or an infringing article. For example, as to one set of transactions “the documents leave open the possibility that Hi-Lux had a choice as to the electronic speed sign supplied, leaving it free to perform the relevant contract without infringing the claims of the Patent”.

There was also an innocent infringement defence raised which, if there had been a finding of infringement, would likely have absolved the respondents from any pecuniary liability for a significant period of alleged infringing activity. The primary point here was that VicRoad’s September 2001 specification was not specific to any project and required a flashing annulus but did not indicate that any patent was pending (or likely to be pending noting Axent did not file its provisional patent application until October 2001). There was no other basis for the respondents to consider there to be a patent in force in respect of the alleged invention until they received a copy of the patent in 2016. Nevertheless, had it been necessary, Kenny J would have invited Axent to provide submissions as to why the discretion in section 123 should not be exercised in the respondents’ favour. As noted above, however, due to the cessation of the patent which was not restored until 2016, Axent already had difficulties seeking relief in respect of much of that innocent infringement period in any event.

Her Honour also considered the defence under section 119(1) of the Act, prior to its amendment to expressly provide for non-infringement where the infringer had taken definite steps to exploit the infringing product prior to the priority date of the claims and to define “exploit” to now include supply and sale of the product. The respondents contended that, prior to amendment of section 119, the expressions “making a product or using a process” in s 119(1)(a) and “make that product, or use the process” in s 119(1)(b) should be construed to cover the sale and supply of the product or process. Her Honour held that was not the case. Accordingly, as the respondents were not “making or using” their infringing sign before the priority date, the defence did not arise.

Furthermore, her Honour considered that, notwithstanding that Compusign had designed a prototype sign and had demonstrated it to potential customers, that would not amount to having taken “definite steps” to make or use the product. Her Honour found that “Compusign Australia’s prototype […] had been created with a view to further development. This is plain enough from Mr Riquelme’s evidence, which I accept, that Mr He had told him “modifications would be made in order to meet a customer’s particular requirements”. The evidence strongly indicates that, as at the priority date, the prototype had not reached a form of a final product. It certainly had not reached the stage where […] Compusign Australia was about to make an infringing variable speed limit sign.” This finding shows how difficult it can be to establish the section 119 defence.

As to novelty of the invention in light of the VicRoads September 2001 specification referred to above, Axent made various assertions. First, it denied the September 2001 specification had been made publicly available. Her Honour put aside an interesting debate as to whether a document could be described as publicly available if it could be obtained by a Freedom of Information Act request. That was because her Honour found that the specification was made publicly available when sent to manufacturers who asked for it in order for them to seek a “type approval”, with no imposition of confidentiality over the specification.

Next Axent relied on section 24 of the Act, namely that the September 2001 specification’s disclosure should be ignored as comprising “any information given by, or with the consent of, the nominated person or the patentee, or his or her predecessor in title, to any of the following, but to no other person or organisation: (i) the Commonwealth or a State or Territory, or an authority of the Commonwealth or a State or Territory”: section 24(2)(a)(i) of the Act. Axent contended that this provision applied not only to information given to an authority of the State (here, VicRoads) but also to persons to whom the State then passed that information (here, the manufacturers, given the September 2001 specification for “type approval”).

Her Honour disagreed. Her Honour found that the words “but to no other person or organisation” indicated that the defence was only applicable to the information given to VicRoads, not VicRoads then giving that information to someone else. The exception in section 24(2) was narrow and the disclosure that Axtent was concerned about was really to be addressed by section 24(1).

Axent sought to rely on section 24(1)(b) which excludes from novelty or inventive step considerations, information “made publicly available without the consent of the nominated person or patentee, through any publication or use of the invention by another person who derived the information from the nominated person or patentee or from the predecessor in title of the nominated person or patentee; but only if a patent application for the invention is made within the prescribed period”. However, Axent had disclosed to VicRoads the flashing annulus sign and a person from VicRoads gave evidence that he thought it reasonable to include that sign in the September 2001 specifications and that Axent was not unhappy about that. Her Honour inferred that Axtent wanted the feature included as a requirement in the specification and so positively consented to its inclusion. In the result section 24 did not apply, and the September 2001 specification was found to have anticipated various claims of the patent.

Finally, as to inventive step, her Honour concluded that all of the claim lacked an inventive step. Her Honour did so without reference to the September 2001 specification because, her Honour found, there was no evidence that a person skilled in the art would have ascertained, understood and regarded the document as relevant. That is a somewhat curious result given it was a specification available from VicRoads for manufacturers seeking a “type approval” before the priority date.

Justice Kenny’s primary finding on inventive step was that the invention as claimed did not “overcome a difficulty or cross a barrier”. Her Honour found that “no problem was overcome or barrier crossed by the adoption of a partially flashing annulus as the conspicuity feature to draw a motorist’s attention to the need to reduce speed”. Her Honour pointed to the use of flashing lights in the corners of the signs as a well-known and efficacious means of communicating information to a motorist and that the use of a flashing annulus “was no more effective as a means of communication at the priority date than the use of flashing amber lights”, that it involved costs savings or overcame some perceived technical difficulty. Finally, her Honour observed that the ordinary skilled worker was aware that there were options, including a flashing annulus, to draw a motorist’s attention to the need to slow down indicating that “a person skilled in the art would have taken the steps leading from the prior art to the claimed invention as a matter of routine”.